Here are notes from Infovores.

Category Archives: institutional economics

The paradox of accountability

Accountability means having our ideas and actions evaluated by others, with those evaluations having consequences. The paradox of accountability is that everybody needs it but nobody wants it.

Everybody needs accountability in order to stay on track. Without effective accountability, individuals and organizations become weak and corrupt.

Nobody wants accountability, because it limits our autonomy. Whether our intentions are good or not, our autonomy is constrained by those who hold us accountable.

Because nobody wants accountability, we try to counteract mechanisms that are designed to create accountability. A CEO is supposed to be accountable to shareholders via the board, but the CEO tries to get around this by “stacking the board.”

Some remarks:

1. With any organization, you can study its accountability mechanisms. Who set them up? What concerns were they trying to address? How well do the mechanisms work? What are their weaknesses?

2. One can interpret institutional history as an evolutionary struggle to establish and evade accountability mechanisms. Organizations respond to corruption by trying to adopt more robust accountability mechanisms. Individuals try to increase their autonomy by finding ways around those mechanisms.

3. The 2008 financial crisis exposed a weak link in the accountability system in an unexpected place: the credit reporting organizations, like Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s. The buyers of mortgage securities were looking for AAA ratings for regulatory purpose only, not because they truly wanted to be certain that the securities were highest quality. The regulators treated the AAA-rated securities very leniently in terms of bank capital requirements, thinking that the credit reporting organizations were more accountable than was actually the case.

4. It seems to me that our society is collapsing because accountability mechanisms are falling apart.

Professors don’t give students bad grades, and students wish to abolish grading entirely. When they graduate, they long to work in the non-profit sector, where for the most part you are accountable for intentions and not results.

The professors themselves are not accountable for doing rigorous work. They just have to worship the diversity religion.

We are losing the small-business sector, which is most accountable to customers. We are replacing it with large corporations that are accountable to government for bailouts and to the social justice mob for approval.

The formal sector and the informal sector

Here’s are some columns from a table from the World Employmentand Social Outlook: Trends 2020 published by the International Labour Organization in January 2020. As the report points out, around the world about 60% of workers have informal jobs; in low-income countries, it’s more like 90%

Read the whole post. The ability to cooperate in groups above the Dunbar number is extremely important for economic development. You might hate big corporations, but they are actually a miracle of civilization, as Tim and others have pointed out.

On law, legislation, and Leoni

From my latest essay.

The legal setting differs from the market setting in that the legal setting is an arena of conflict. If I need someone to fix my car, I enter the market arena. The mechanic and I agree on a price, and ordinarily both of us walk away happy: my car is fixed, and the mechanic has been paid. The transaction involves mutual satisfaction.

But suppose that my car is still not working properly when I go to the mechanic to pick it up. The mechanic claims to deserve to be paid, and I claim otherwise. Now we are in the arena of conflict. The legal system is there to provide a peaceful, fair way to resolve this conflict.

This means that a key virtue of a legal system is legitimacy. The legal system does not need to be perfect. What it needs is acceptance, so that a court ruling ends the conflict, peacefully. So you cannot prove that common law is superior to legislation, or conversely. You cannot know until you know which system has the most public acceptance.

Dealing with complex social problems

Despite our current state of social decay, a systems approach could help rebuild habits, manners, and morals that have fallen into disrepair. Because it takes a comprehensive view of social problems, such an approach would entail a multi-step process.

First, it would bring together a wide range of concerned actors from government, philanthropies, religious institutions, NGOs, the private sector, and local communities to build a common picture of the current reality. Second, these stakeholders would be given an opportunity to lay out their competing explanations for why the complex problems persist and even grow despite decades of attempts to improve conditions. Third, these different perspectives would be integrated into a much more comprehensive picture of the whole system, including underlying drivers of the problems. Fourth, with this comprehensive picture, stakeholders would see how various well-intended efforts to solve the problems in the past often made things worse. Finally, they could use this knowledge to forge a new vision of how the future might unfold through a wide range of complementary initiatives that can combine to produce sustainable, system-wide change.

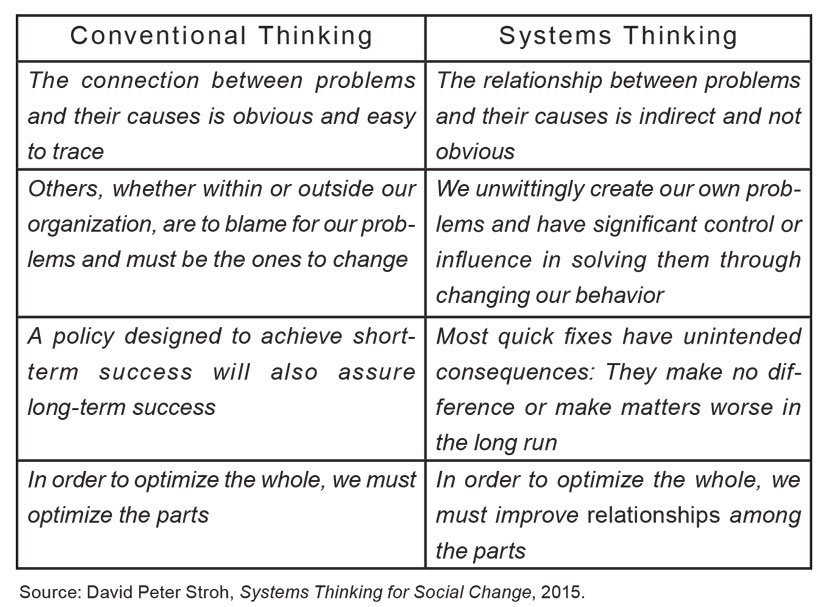

Borrowing from David Peter Stroh, Kaplan contrasts conventional thinking with systems thinking.

Note that the first point highlights the oversimplification bias that is embedded in conventional thinking.

Sentences about Puerto Rico

From commenter Handle.

it was already in really bad shape before the storm. But Puerto Rico has had just about as many institutions of American government as it possible for any slightly-foreign, Spanish-speaking place to have for a long, long time. It obeys federal law, gets generous federal subsidies, has elections, courts, local offices of all the federal agencies, military bases, etc. Puerto Ricans are American citizens, have open borders with the rest of the U.S., and so forth.

And yet all those institutions don’t seem to have done the island much good in terms of convergence: it always seems to trail the rest of the US by the same proportion economically, consistently lags much more educationally, local governance is poor quality, and they are effectively bankrupt – though this could also be said for some of the worst mainland states (Connecticut) and cities (Chicago). They have been going through the motions, but not getting the results.

South Korea and North Korea are a case of similar people, different institutions. Are Puerto Rico and the U.S. a case of similar institutions, different people?

Russ Roberts on emergent order

Then there are things that are out of our control but that happen on their own through a natural process no human being intends or designs. Breathing. The healing of a paper cut. Staying attached to the earth rather than floating off into space. We don’t have to lean into the curve as we go around the sun to keep the earth on orbit. No human being is in charge of making sure the sun comes up tomorrow. When it rains, we may be frustrated if we had hoped to go on a picnic in the park but there is no one to blame. And if it’s an especially beautiful day, we may thank God or simply be glad to be alive. But there is no person we owe thanks to.

There is more at the link.

Yuval Levin on Concentration of Power

causes for worry on this front are by no means limited to the presidential contenders. They are evident in our institutions, and not only those dominated by the Left. Indeed, the willful weakness of the Congress (which has been largely run by Republicans for two decades) and of the state governments (most of which are run by Republicans) may be the most significant problems our system confronts. Congress routinely delegates its power and abides executive overreach for policy or political ends. And while some state leaders have certainly pushed back against federal overreach at times, on the whole the states have accepted the bargain of “cooperative federalism”: From healthcare to education to transportation and beyond, federal dollars flow to the states in return for power flowing to Washington.

I am inclined to look at structural reasons for this. On states vs. the Federal government, I think that the big fact is that the Federal government can borrow to fund its operations. If we had not broken the balanced-budget norm that prevailed up until the Second World War, we might have a more balanced relationship between Washington and the states.

Congressional weakness comes from the imbalance between accountability and authority. Senators and Representatives hear from their constituents very day. They are lobbied by interest groups that hold the power of the campaign-finance purse over them. This makes our representatives in Congress feel very accountable. If they exercise authority, they fear the consequences.

For the executive branch, the situation is reversed. The agencies that issue regulations and administer programs have relatively more authority and relatively less accountability. The courts also have gained in authority with less accountability. That creates an incentive to exercise ever-increasing power.

Another factor is mass media. This concentrates the public’s attention on the President, who is much better able to gain popular support. In a mass media age, we have tended away from separation of powers and toward elected monarchy.

Oliver Hart on Vertical Integration

if I’m Firm A, I’m acquiring control over all the non-human assets that Firm B had, which might be machines, land, buildings, but also less physical things like patents, copyrights, existing contracts that Firm B had with other firms. The name of Firm B, all sorts of things like that.

To the extent that the initial contract was incomplete, and will always be incomplete, whatever contract we write will be incomplete. Having, owning those things now means that I can get to decide how they are used to the extent that the contract was silent about that. Whereas previously, it was the owner, Firm B, that wasn’t me, who had those rights. That’s a real change. That, we would argue, is one of the key reasons that Firm A is acquiring Firm B, to get those residual control rights.

Pointer from Mark Thoma.

The whole interview is interesting. Hart shared the 2016 Nobel Prize. Of the last 10 years of Nobel Prizes, I could make a case that 6 have been awarded for the study of institutional arrangements.

2007 Hurwicz, Maskin, and Meyerson: mechanism design

2008 Krugman: agglomeration

2009 Ostrom, Williamson: governance

2012 Roth, Shapley: mechanism design

2014 Tirole: industrial organization and regulation

2016 Hart and Holmstrom

That is a notable trend, and I think it is a good one. When you focus on institutional arrangements, there is more of a tendency to say that the economist’s first challenge is to understand how things operate in the real world. A lot of other areas of focus tend to find the economist creating a hammer (a particular mathematical technique, or a model that is fun to work with) and looking around for nails in the real world that may or may not exist.

Pete Boettke on Expertise

The problem with experts isn’t that individuals can have superior judgement to others, or that one can earn authority through judicious study and successful action. The problem is an institutional one, and institutional problems demand institutional solutions. In the case of the Levy/Peart and Koppl stories, the problem results from monopoly expertise that produce systemic incentives and social epistemology which is distortionary from the perspective of correct policy response.

Read the whole post. Pointer from Don Boudreaux.